Chinese Canadians are one of the largest ethnic groups in the country. In the 2021 census, more than 1.7 million people reported being of Chinese origin. Despite their importance to the Canadian economy, including the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR), many European Canadians were historically hostile to Chinese immigration. A prohibitive head tax restricted Chinese immigration to Canada from 1885 to 1923. From 1923 to 1947, the Chinese were excluded altogether from immigrating to Canada. (See Chinese Immigration Act.)

Since 1900, Chinese Canadians have settled primarily in urban areas, particularly in Vancouver and Toronto. They have contributed to every aspect of Canadian society, from literature to sports, politics to civil rights, film to music, business to philanthropy, and education to religion.

This is the full-length entry about Chinese Canadians. For a plain-language summary, please see Chinese Canadians (Plain-Language Summary).

Immigration Patterns

The first Chinese people to settle in Canada were 50 artisans who accompanied Captain John Meares in 1788 to help build a trading post and encourage trade in sea otter pelts between Guangzhou, China, and Nootka Sound, British Columbia. The Spanish, who were seeking a trade monopoly on the West Coast, drove out Captain Meares, leaving many of the Chinese crew members to settle in the area. Some married Indigenous peoples.

In 1858, Chinese immigrants began arriving in the Fraser River valley from San Francisco, as gold prospectors. Barkerville, British Columbia, became the first Chinese community in Canada. By 1860, the Chinese population of Vancouver Island and British Columbia was estimated to be 7,000. Many of the first Chinese immigrants arrived from rural areas in southern China. They laboured under appalling conditions to build the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR). Between 1880 and 1885, 15,000 Chinese labourers completed the British Columbia section of the CPR, with more than 600 perishing under adverse working conditions. Largely because of the Trans-Canada railway, Chinese communities developed across the nation.

At the turn of the 20th century, there were 17,312 Chinese settlers in Canada. From 1988 to 1993, 166,487 Hong Kong immigrants settled in Canada, with Ontario (50.57 per cent) and British Columbia (26.7 per cent) receiving the bulk of these new citizens. By 2001, 82 per cent of people of Chinese origin lived in one of these two provinces. According to the 2021 census, there were more than 1.7 million people of Chinese ancestry living in Canada.

Origins and Emigration

During the 19th century, war and rebellion in China forced many peasants and workers to seek their livelihoods elsewhere. Rural poverty and political upheavals stemming from the First Opium War (1839–42) and the Hakka led T'ai P'ing Rebellion (1850–64) caused widespread Chinese emigration. Historically, the majority of migrants came from the four districts or counties (Tai Shan, Xin Hui, Kai Ping, En Ping) in the Pearl River delta of Guangdong province, between Guangzhou and Hong Kong. In these areas, a tradition existed of seeking opportunities overseas, sending money back to support relatives in China, and eventually returning, if possible.

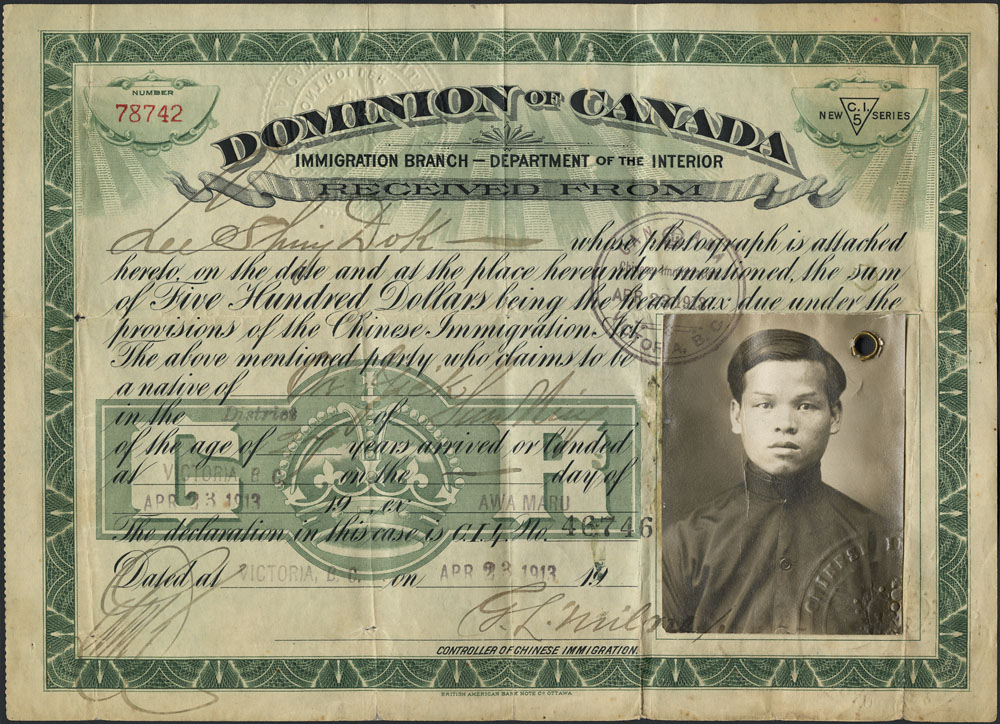

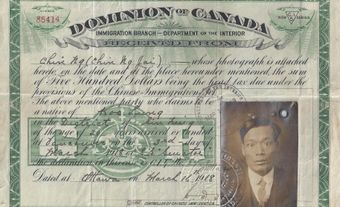

The major periods of Chinese immigration (from 1858 to 1923 and since 1947) reflected changes in the Canadian government’s Immigration Policy. From 1885, Chinese migrants had to pay a $50 “entry” or “head” tax before being admitted into Canada. The Chinese were the only ethnic group to pay a tax to enter Canada. By 1900, in response to agitation in British Columbia, the Liberal government further restricted Asian immigration by raising the head tax to $100. Politicians greeted this decision with anger in British Columbia and demanded it be increased to $500. The federal government appointed a Royal Commission on Chinese and Japanese Immigration (1902). It concluded that the Asians were “unfit for full citizenship... obnoxious to a free community and dangerous to the state.” After the 1903 session of Parliament passed legislation raising the head tax to $500, the number of Chinese who paid the fee in the first fiscal year dropped from 4,719 to eight. Soon afterwards, Chinese immigration increased, and on 1 July 1923 (known to many Chinese Canadians as “Humiliation Day”), the Chinese Immigration Act was replaced by legislation of the same name that virtually suspended Chinese immigration. The new Act banned most Chinese immigrants from entering Canada. The only exceptions were to be merchants, diplomats, and foreign students. Ethnic Chinese people with British nationality were also restricted from entering Canada.

Largely because of the head tax, the cost of bringing a wife or aged parents to Canada became prohibitive. Therefore, Chinese men typically came alone and lived as bachelors in Canada. In 1931, out of a total Chinese population of 46,519, only 3,648 were women. In the late 1920s, it was estimated that there were only five married Chinese women in Calgary and six in Edmonton.

In 1947, the discriminatory legislation was finally repealed. Since then, immigration of families has been the rule, with the majority of individuals emigrating from Hong Kong, Taiwan, and the People's Republic of China. Other Chinese immigrants have come from South Asia, Southeast Asia, South Africa, the Caribbean, and South America. These different communities speak English and Mandarin, Fukien, or Cantonese, are well educated, and frequently possess financial resources and professional skills.

Settlement Patterns

Since 1900, Chinese Canadians have chosen to settle in urban areas, and are now concentrated in the largest cities. Contrary to stereotypes of Chinatowns as “overcrowded ghettos,” the communities that developed in the 19th and 20th centuries were significant places for businesses and families. They became the heart and soul of Chinese Canada and were a safe bastion from the hostile and racist environment that surrounded them (see Victoria Chinatown; Toronto Chinatown; Montreal's Chinatown). In particular, Vancouver's Chinatown during the exclusion era (1923–47) became a thriving economic and social destination that was home to many Chinese Canadians on the West Coast.

In Vancouver, restrictive covenants prevented the Chinese from buying property outside the Chinatown area until the 1930s. During the 1880s, the vast majority of Chinese Canadians lived in British Columbia. By the 1940s, almost 50 per cent of the Chinese Canadian population lived on the West Coast. Although Chinese communities have developed rapidly in other urban centres, approximately 70 per cent of Chinese Canadians still lived in Toronto and Vancouver in 2006.

Economic and Financial Life

Upon arrival in British Columbia, Chinese emigrants were involved in various kinds of work. Some worked in the gold fields, often on abandoned claims. Others became cooks, laundrymen, teamsters, domestic servants, and merchants, providing auxiliary services to mining communities. Between 1880 and 1885 the primary work for Chinese Canadian labourers was on the railway. During the next 40 years, Chinese people became involved in the toilsome labour behind an industrializing economy. Skilled or semi-skilled, Chinese Canadians laboured in British Columbia sawmills and canneries; others became market gardeners or grocers, pedlars, shopkeepers, and restaurateurs.

A “credit-ticket” system evolved whereby Chinese lenders in North America or China would agree to pay the travel expenses of a migrant who was then bound to the lender until the debt was repaid, even though these contracts were not legally enforceable in Canada. The work of Chinese industrial labourers was often organized under contract and sometimes involved Chinese work gangs. At the turn of the 20th century, Chinese cannery bosses were frequently hired on contract. They, in turn, recruited workers and assumed the financial risk of low production yields. From the 1880s, this practice was also employed in railway construction.

Chinese immigrants were considered a source of cheap labour to be exploited because of their economic desperation and acceptance of low pay from Canadian employers. Chinese Canadian labour was characterized by low wages (workers usually received less than 50 per cent of what Caucasian workers were paid for the same work) and high levels of transience. (See also Immigrant Labour.)

The earliest Chinese professionals tended to serve primarily the Chinese community. In British Columbia, Chinese professionals were barred for years from practicing such professions as law, pharmacy and accountancy. The first Chinese-Canadian lawyers were called to the Bar only in the 1940s. Since then, discriminatory laws have been repealed. Nevertheless, even in the 1980s, Chinese Canadians were still heavily involved in the service industry. At the turn of the 21st century, Chinese Canadians could be found in many occupations, such as television reporter, jazz musician, classical dancer, novelist, police officer, and politician, as well as in the traditional careers of educator, scientist, and entrepreneur.

Social Life and Community

Although some tension between new and old immigrants exists, the network of kinship is still strong. During the 19th century, and most of the 20th, Chinese Canada reflected such cultural traditions as the kinship system (based on ancestral descent), the joss house (or temple), and Chinese theatre. Communities have also incorporated North American characteristics. Chinese communities in Canada have generated “voluntary” associations that are adapted from models in China that provide personal and community welfare services, social contact, and political activity. Rural Chinese immigrants have typically had to adapt to urban conditions, and these associations have helped migrants adjust to a new culture and to manage prejudice and discrimination and racism.

During the early decades of the 20th century, fraternal-political associations such as the Guomindang and the Freemasons were involved in Chinatown politics and community issues. Larger Chinese communities established Chinese Benevolent Associations as the apex of their organizational structures; these organizations adjudicated disputes within the community and spoke for the community to the outside world. None of these organizations, however, has been an effective national voice. Typically Canadian organizations such as the Elks, Lions, Masons and veterans' associations have appeared within Chinese communities.

Because of the influx of Chinese emigrants from the global diaspora, community organizations reflecting Chinese people from Cuba, India, Jamaica, Mauritius, Peru, etc. have created a dynamic presence in Canada. Immigrants from the People's Republic of China have organized into many associations. The CPAC (formerly the Chinese Professionals Association of Canada) reports having a membership of more than 30,000 in 2019. Professional organizations are gradually replacing the old Guomindang, Freemasons, and Chinese Benevolent Associations.

The original Chinese communities were isolated from white culture for several reasons. The Chinese have often been stereotyped as “sojourners;” that is, in Canada temporarily to obtain financial security for relatives in China. During the 19th century especially, the Caucasian society of British Columbia perceived Chinese people as people who could not be assimilated; certain aspects of Chinese life and culture in Canada reinforced the xenophobic notion that Chinese communities posed a threat to Caucasian society.

The poverty-stricken living conditions in which Chinese Canadian workers lived were denounced as conduits for disease that might spread to Caucasian neighbourhoods. For example, Dr. Roderick Fraser, medical health officer of Victoria, BC, stated in the 1902 Royal Commission on Chinese and Japanese Immigration report that, “I think the Chinese are more unhealthy as a class than the same class of white people.”

Countering Dr. Fraser's negative statement, the San Francisco-based Qing Dynasty Consul General Huang Cunxian in 1885 told a Royal Commission on Chinese Immigration:

“[...] it is charged that the Chinese do not emigrate to foreign countries to remain, but only to earn a sum of money and return to their homes in China. It is only about thirty years since our people commenced emigrating to other lands. A large number have gone to the Straits' Settlements, Manila, Cochin China and the West India Islands, and are permanently settled there with their families. In Cuba, fully seventy five per cent have married native women and adopted those Islands as their future homes. Many of those living in the Sandwich Islands have done the same.[...]

There is quite a large number of foreigners in China, but few of whom have brought their families, and the number is very small indeed who have adopted that country as their future home.

You must recollect that the Chinese immigrant coming to this country is denied all the rights and privileges extended to others in the way of citizenship; the laws compel them to remain aliens.I know a great many Chinese will be glad to remain here permanently with their families, if they are allowed to be naturalized and can enjoy privileges and rights.”

Fears of disease (e.g., cholera and leprosy), white reactions to overcrowded living conditions in Chinatown, the introduction of the drug trade, and an obsessive concern with Chinese gambling habits all maintained the prejudice that the Chinese, as one senator speaking for white residents of British Columbia explained, “are not of our race and cannot become part of ourselves.” In addition, the discriminatory laws and attitudes at the time prevented many Chinese from considering Canada as their permanent home. Thus, the transitional mentality, reinforced by Canadian legislation that excluded Chinese immigration to Canada between 1923 and 1947, prevented easy immigration of Chinese families and precluded their participation professionally, socially or politically in the dominant society. It was not until 1947 that Chinese Canadians were granted citizenship.

Religious and Philosophical Life

Religion for Chinese Canadians has commonly been expressed in private. Generally, it has declined in practise. In the 2001 census, Chinese communities were significantly different from the rest of the Canadian population, reporting that 58 per cent had no religious affiliation, compared to 15 per cent of the Canadian population as a whole. The proportion of Christians in the Chinese Canadian population rose from 10 per cent in 1921 to 60 per cent in 1961, but declined to 26 per cent by 2001. Other Chinese Canadians follow Buddhist, Islamic and other faiths. Among Canadians of Chinese origin who maintain religious affiliation, 34 per cent were Buddhist, 28 per cent Catholic and 22 per cent belonged to a Protestant denomination. Although membership in many Christian churches has declined, Chinese membership in the Baptist Church has continued to grow. Many Chinese Canadians are also followers of philosophical Taoism, Zen Buddism, and qigong.

The major Chinese festival is the Lunar New Year (February or late January), which is celebrated in many Chinese communities with firecrackers and lion and dragon dancers. Other important festive days are Clear and Bright, a springtime sweeping of the graves of ancestors, and Mid-Autumn, also known as the Moon Festival, symbolizes harvests and family reunions.

Cultural Life

Since the mid-1980s, Chinese Canadian culture has blossomed. This robust culture has begun to develop not just as a reflection of China, Hong Kong, or Taiwan, but with reference to the varied experiences of Chinese communities in Canada. Major writers influencing the evolution of a new and dynamic literary tradition include Evelyn Lau, Wayson Choy, Larissa Lai, Denise Chong, Paul Yee, Jim Wong-Chu, and Vincent Lam. Filmmakers such as Laiwan, Christina Wong, Colleen Leung, Dora Nipp, Tony Chan, Yung Chang, William Dere, Richard Fung, Julia Kwan, Karin Lee, Mina Shum, Michelle Wong, Paul Wong, and Keith Lock have been at the forefront of a new cinematic tradition conditioned by and infused with the experiences of Chinese Canadian communities. The doyen of Chinese Canadian filmmakers, Keith Lock, directed The Ache (2009), a critically acclaimed feature that explored the dynamics of fantasy, perception and spirits. Irene Chu was the executive producer of a 20-part series for OMNI Television that explored the lives of Chinese immigrants in Canada. Entitled Once Upon a Time in Toronto (2009), it was the first major joint Chinese/Canadian production of a television drama series.

Canadian film and theatrical actors of Chinese heritage include Tommy Chong (Up in Smoke), Kristin Kreuk (Smallville), Byron Lawson (Snakes on a Plane), Linlyn Lue (Degrassi: The Next Generation), Jennifer Tilly (Jennifer E. Chan, Bullets over Broadway); Meg Tilly (Agnes of God), Valerie Sing Turner (Da Vinci's City Hall, La Femme Nikita), Norman Lup-Man Yeung (Pu-Erh), and Françoise Fong-Wa Yip (Rumble in the Bronx).

One of the first influential literary and political magazines to create a dynamic venue for many Chinese and Asian Canadian writers, activists and filmmakers was Asianadian: An Asian Canadian Magazine (1978–85). Such well-known authors as Sky Lee and Paul Yee published their first writings in that magazine, which was co-founded by Tony Chan in Toronto. A online version of Asianadian is the Toronto-based Ginger Post (2009) founded by Wei Djao and Lian Chan.

Musicians Sean Gunn (Running Dog Lackey) and Trevor and Matt Chan (no luck club), and composer Darren Fung (Stinky Rice Studios), are some of the heirs to the Chinese Canadian jazz tradition, which began with the swing band, Celestial Gents (1937–41). Hope Lee and Ka Nin Chan are two of Canada's most distinguished contemporary composers.

Education

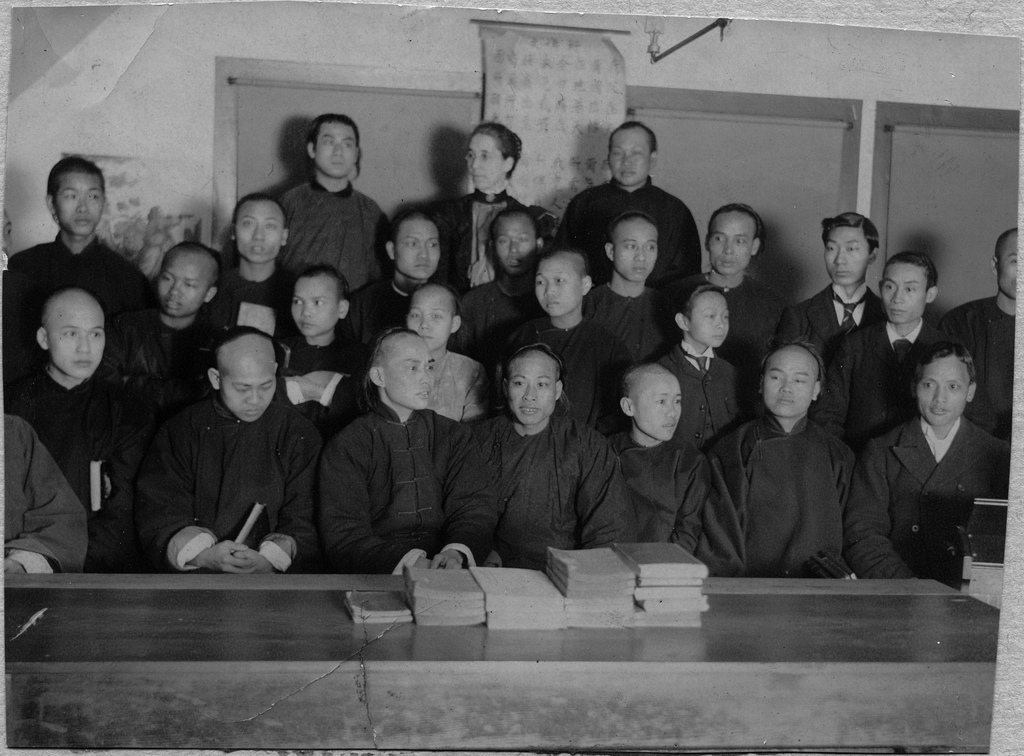

Chinese schools in Canada date from the 1890s. At their peak in the 1930s, there were 26 across the country. In British Columbia, they gained particular importance when attempts were made to segregate Chinese Canadian children. Even when professional fields were closed to them after graduation, Chinese Canadians were never legally prohibited from attending universities. With a rise in affluence and professional character among certain Chinese communities in the 1960s, much larger numbers of Chinese Canadians sought higher education. In 2001, more than one quarter had earned a university degree.

English language education plays a major role in Chinese Canadian families, particularly for recent immigrants. The result has been an influx of Chinese Canadians in many professions, including engineering, the sciences, research, medicine, pharmacy, law, and higher education. Emphasis on education is a long-standing feature of Chinese life and the result of the Confucian tradition of learning and scholarship. The Chinese language is still considered a significant part of education, especially with the growing economic prominence of China.

To educate the general public about the Chinese in Canada, the Chinese Canadian Historical Society of British Columbia was created in 2004. The Richard Charles Lee Canada-Hong Kong Library at the University of Toronto is a dedicated resource centre for Chinese Canadian studies. The Chinese Culture and Education Society of Canada (based in Toronto) teaches Chinese and seeks to develop education and cultural exchanges between Canada and China.

Politics and Civil Rights

Chinese communities in Canada have always been politically active. During the 19th century, they fought discrimination and exclusion. One of the first civil rights organizations to support Chinese Canadians was the Victoria Workingmen's Protection Association, established in 1876. Its major aim was to rally against abysmal working conditions and economic restrictions. In 1878, Victoria's Chinese merchants protested against the $60 provincial head tax by petitioning Ottawa to eliminate the fee. Just before the enactment of the 1923 Chinese Immigration Act, the Chinese Association of Canada went to Ottawa to lobby against the bill.

During the Second World War, many Chinese Canadians tried to enlist to fight but were refused by authorities because of their race. Around 150 Chinese Canadians were eventually recruited as commandos in Force 136 to infiltrate Japanese-occupied territories. The recruits included Douglas Jung who would later become the first Chinese Canadian Member of Parliament. For some like Jung, volunteering was seen as a way to push for citizenship rights.

Chinese Canadians gained the vote federally and provincially in 1947. Until the 1950s, community members depended on their association leaders and other intermediaries who had relationships with Canadian politicians to speak on their behalf in Canadian affairs. They later became more active in Canadian politics, particularly for the Liberal Party, partly because of its identification with relaxed immigration regulations. In various places, mayors and councillors of Chinese origin have been elected. Chinese Canadian political firsts include Douglas Jung (Member of Parliament, 1957–62), Peter Wing (mayor of Kamloops, 1966–72), Raymond Chan (federal cabinet minister, first elected in 1993), Ida Chong (provincial cabinet minister in British Columbia, first elected in 2001) and Alan Lowe (mayor of Victoria, 1999–2008). Philip Lee became Manitoba's first Asian lieutenant-governor and Norman Kwong, Canada's first professional Chinese Canadian football player, also became Alberta's first Chinese lieutenant-governor.

The watershed event that politicized the Chinese community in Canada and, in turn, established the Chinese Canadian National Council (CCNC), was the infamous W5 controversy in which CTV aired a segment called “Campus Giveaway” on 30 September 1979. At the heart of “Campus Giveaway” was the allegation that foreign students were taking the place of white Canadians in such career-related university programs as pharmacy, engineering and medicine. Since the “foreign faces” in the report were Chinese, W5's implication was that all students of Chinese origin were foreigners, and that

The head tax has always been a source of grievance in Chinese Canadian communities. Protests and demonstrations calling for an official apology and redress were staged across the nation. Under much community pressure, on 22 June 2006 Prime Minister Stephen Harper offered an apology in Cantonese. An official directive made in Parliament ordered compensation for the head tax of approximately $20,000 to be paid to survivors or their spouses.

Cultural Conservation

The Hong Kong version of modern Chinese culture is very strongly reflected in Chinese Canadian society, yet some traditional values continue. For example, many young Chinese Canadians continue to commit resources to support their parents, and many grandparents live with their children. Institutional care facilities such as the Yee Hong and Mon Sheong nursing care facilities in Toronto have been established in cities across Canada. In large Chinese Canadian communities, professionals tend to sponsor cultural exchanges with China, Hong Kong and Taiwan to encourage the preservation of Chinese culture and to promote the fair representation of Chinese Canadians in the media, among other reasons. Canada-based Beijing and Cantonese opera groups exist and martial arts organizations have flourished.

Language preservation was essential before 1947, when only jobs in Chinatown requiring knowledge of Chinese were open to young Chinese Canadians. Although the use of written Chinese has declined, newspapers continue to be an important form of community expression. Chinese-language papers have long been published in Vancouver and Toronto, and North American editions of Chinese-owned newspapers such as World Journal Daily, Sing Tao and Ming Pao continue to be popular, despite an industry-wide downturn in printed newspapers due to the loss of print advertising. Since Chinese language newspapers solicit advertisement dedicated to Chinese readers only, this lucrative source of revenue can be tapped solely by Chinese-owned newspapers. Other notable newspapers are CC Times, Global Chinese Press and Today Daily News. Chinese language television stations like Fairchild, LS Times and OMNI have also developed in major cities, broadcasting widely-watched Cantonese and Mandarin situation comedies, news, documentaries, and movies.

In the 2021 census, 679,255 people reported having Mandarin as a mother tongue language, and 553,380 people reported having Cantonese as a mother tongue language. (See Chinese Languages in Canada.)

Later Trends in the Chinese Diaspora

According to statistics from Citizenship and Immigration Canada, between 1999 and 2009 the largest number of immigrants to Canada came from the People's Republic of China (PRC). The highest influx was in 2005 with 42,295. By 2010, 36,580 immigrants from the Philippines surpassed the 30,195 from the PRC. Filipinos retained their status as the number one immigrant group to Canada in 2011 with 34,991. The PRC lagged behind with 28,696.

This significant demographic change relegating Chinese immigration to Canada to second spot was the result of the economic boom in China. This caused potential immigrants to stay in their country for work, family and cultural reasons. Likewise, many Chinese Canadians with ties to the PRC and Hong Kong leave Canada for many reasons. With more job opportunities in the PRC and Hong Kong, even those Canadians of Chinese origin have emigrated from Canada to these places.

Those Chinese with Chinese degree credentials who remain in Canada are subjected to the same credential evaluation as any other immigrant. Some Chinese immigrants' lack of credential recognition can be attributed to their inadequate English or French language proficiency and insufficient work experience as well as to the credibility of the Chinese universities from which they graduated.

Changing demographic dynamics in Canada and economic developments in China will have a concerted impact on how Chinese Canadians perceive themselves as Canadians in a global world. Moreover, they will need to discover how they fit in with the growing economic evolution in the People's Republic of China.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom